Music titans, like European royalty, pine for a bygone era

In reading a summary this morning of the record industry’s latest fight with free streaming services, I was struck how much it’s like the laments of former European nobility in the 19th and 20th centuries. Maybe no one lost their head — or had his family wiped out by Boslehvik bullets — but the loss of power is similarly irreversible.

I first researched the industry economics in 2002 while a consultant to Live365 (the earliest free streaming music service). For my technology strategy class at UCI, I wrote a teaching case on the Napsterization of Hollywood, and how both CD unit sales and revenues peaked in 2000 in the face of MP3 piracy.

At the same time, the big six (later five, now three) recording companies consolidated market share from 79% to 83%. They had a cozy oligopoly, the ability to unilaterally set prices, and (as Michael Porter would say) low rivalry. With their limousines and executive suites they were the capitalist equivalent of the 17th and 18th century royalty of Europe.

This morning’s article in the Wall Street Journal was about how the record labels are trying to phase out the access that free streaming services (e.g. Pandora) have to their catalogs:

One major-label executive said he regretted ever having agreed to allow licensees to offer any on-demand listening features free. “In hindsight we made a mistake,” he said.But one paragraph perfectly summarized the economics of what has happened to the industry in the last 15 years:

An average user of free, ad-supported streaming services generates revenue of around $4 a year to record companies, according to one label executive, compared with between $50 and $75 a user in the record-buying age. Spotify subscribers currently pay $120 a year, of which about 70% goes to record labels and music publishers. Users of free services such as Pandora Media Inc. ’s custom radio service far outnumber those paying for Spotify and its competitors.In other words,

- the labels used to have a reliable income stream from the music-buying (teen and young adult) of around $60/year; according to my notes, that totaled $14 billion in the US in 2000

- that has been replaced by customers who listen to free streaming and pay 93% less.

- the labels hope the current generation of customers will be nice enough to upgrade to a membership model that pays as much as their former business model. ($84 in 2014 ≈ $61 in 2000)

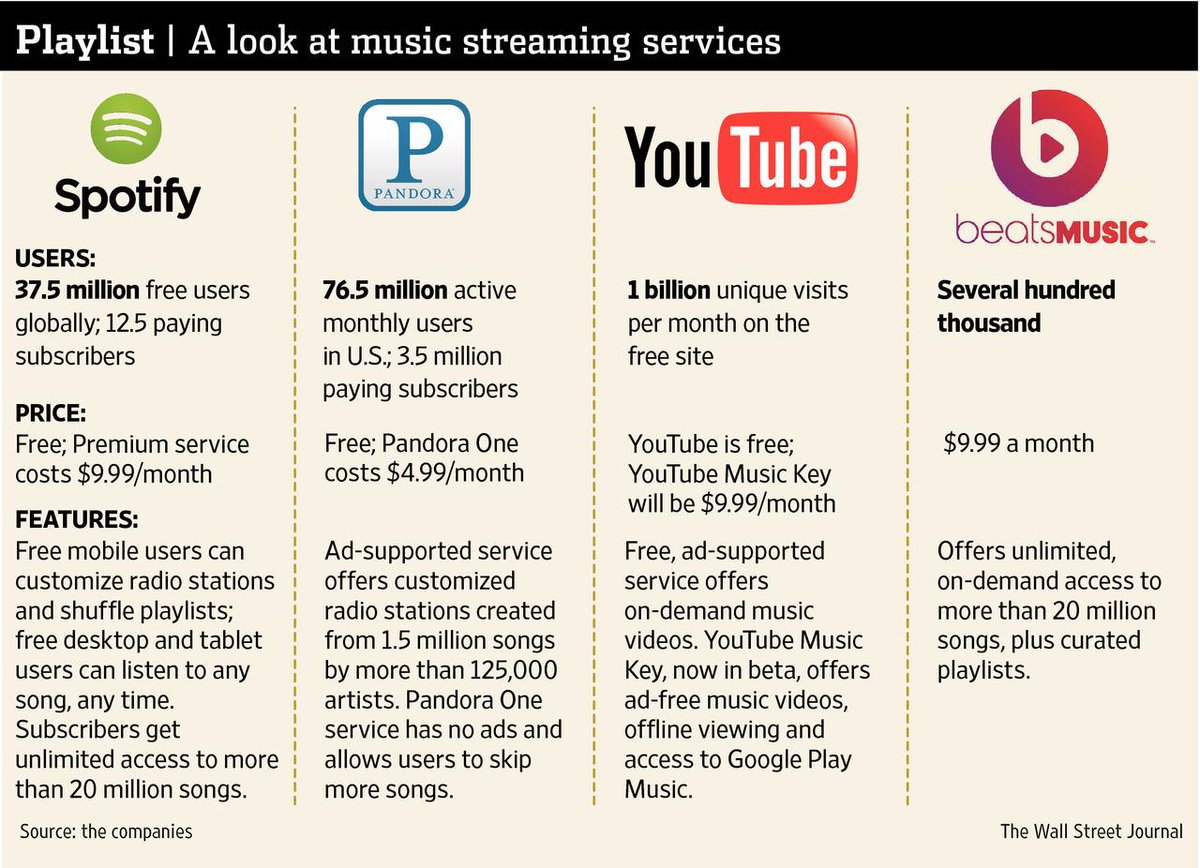

- Spotify (global) 12.5m paid, 25m unpaid

- Pandora (US) 3.5m paid, 73m unpaid

- Beats Music (US) < 0.5m paid

There does appear to be one royalty that is doing well: the elite entertainers. The article reports Taylor Swift asked Spotify to limit her new album (1989) to the paid service, but the company refused. So instead, Swift pulled her album from Spotify and sold 1.7 million copies in its first two weeks — half of those as physical CDs — and perhaps the only album that will be RIAA platinum this year.

Similarly, Garth Brooks (3rd in US record sales after the Beatles and Elvis) created a new download service called GhostTunes — to host his own latest album. (It also has music by Swift, Pink Floyd and the Foo Fighters). The many zombie bands from the 60s and 70s also seem to be able to generate sales — perhaps from price-insensitive geriatric baby boomers — that insulate them from the pressures of the current market.

So — as my class used to conclude 12 years ago — the ability to set your prices without fear of competition is something every firm aspires to. (PayPal alum Peter Thiel has been saying the same thing recently in his new book, Zero to One). The problem is, there’s no way that Hollywood will ever get their monopoly pricing power back — any more than Luke Skywalker will get back his hand, his dad and his innocence, or that the original Beatles will be finally reunited in the flesh.

![[feed]](http://photos1.blogger.com/x/blogger2/6971/993546936938810/1600/z/962294/gse_multipart3851.gif)